I think differential privacy is beautiful!

Why are we here?

Protecting the privacy of data is important and not trivial. To help make sense of things here, the Fundamental Law of Information Recovery becomes useful which states: Overly accurate estimates of too many statistics can completely destroy (data) privacy. Another example that provides a good incentive for why privacy is important is the ability of LLMs to memorize data which is an undesirable outcome as it risks the leak of PII.

Before discussing DP, I’d like to spend a few words on giving some intuition behind The Privacy vs Utility Tradeoff:

Whenever we make some use of the data at hand and hence, learn something useful from it, we lose out on some privacy. Elaboratively, let’s say we begin by learning only one statistic from a collection of datapoints at hand, even then we lose out on some privacy as far as the individual data points are concerned. This privacy loss keeps amplifying as we keep on learning more useful information from the data, and importantly, this is inevitable.

Conversely, to be able to maintain full privacy of the data, we will have to give up on learning “anything” useful from it. Total privacy = No learning.

Differential Privacy: A High Level Intuition

First of all, what even is privacy in a “non-subjective sense”?

[Why non-subjective?: To me, getting the data on my handedness leaked is not a breach of my privacy. I don’t mind it but someone else might consider it as a privacy violation if their handedness is to get leaked.]

DP answers this question in a concrete mathematical equation, but let’s first get the intuition right. Consider an attacker who is interested in knowing my handedness and somehow gets access to the following information:

- I, along with 999 other individuals are participating in a survey whose end result shall be the percentage statistics of people belonging to the left-handed category.

- The attacker is very strong and somehow was also able to get their hands on the handedness of the other 999 people.

Voila! Let the survey results get published and the attacker will be able to learn my handedness with 100% accuracy (I am ambidexterous btw and I don’t mind sharing it but you get the gist :)).

How can we prevent this?:

Keeping the above example in mind, consider a Mechanism \( M \) (the survey) and a dataset \( D \). The Mechanism \( M \) processes \( D \) and produces some output \( O \). By virtue of \( M \), it’s possible for the attacker to look at \( O \) and recover my info using it. What differential privacy does is that it adds some form of noise (or randomness) to \( M \) as a result of which the attacker is no more able to make such deductions using the output \( O \) that’s a result of the “Differentially Private Mechanism \( M \)”. I mean they are free to make such deductions ofcourse, but those will not be as accurate as we discussed above and it is all by virtue of the noise we add to \( M \).

[What this noise is, where and how it’s added and how it works to provide mathematical privacy guarantees is something I’ll circle back to in a minute.]

Elaborating on it:

If \( M \) is differentially private, then the output we will get out of \( M \) in case I am right handed and the output we get out of \( M \) in case I am left, are “similar”.

I want to define here concretely what “similar” actually means: It means that we can get the exact same output out of \( M \) in both these cases with a “similar probability”. And hence, the attacker can never be 100% sure of my handedness and so the Mechanism \( M \) protects my privacy. A key thing to note here is that it is the Mechanism \( M \), and not the output \( O \), that is differentially private.

DP is strong!

Before diving in the Math, there are two very interesting properties that need some clarification here:

Goal of the attacker - DP is capable of protecting all kinds of info. Say, if there’s a different setup wherein there are two datasets \( D1 \) and \( D2 \) between which I am present in only one, and the goal of the attacker is to identify the dataset which I am a part of. DP protects my privacy against this and many other kinds of potential attacks.

Strength of the Attacker - The attacker that we considered above was quite strong (so much so that the two cases we considered differ only in one data point which is mine), and even then we were able to protect my data using DP. The point here is that DP protects privacy no matter how strong the attacker is, what they know and whatever their capabilities are.

I hope this section was helpful in building some notion of what DP is and how it defines and protects privacy.

The Math

I will now write in an equation what we discussed above in words. This equation is actually the standard definition of differential privacy and the goal of the next few paragraphs is to decode the formal definition of DP and understand how that relates to the intuitive understanding of privacy that we got above. If the equation does not make 100% sense at the first read, please hold on and read and re-read more.

Definition

Consider a mechanism M, and two datasets \( D1 \) and \( D2 \) that differ only in one single datapoint. The mechanism \( M \) is ε-differentially private if, for all such datasets \( D1 \) and \( D2 \), the following holds:

$$ \mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right] \le e^\varepsilon\cdot\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right] , ε>0 $$

and, it holds for all possible output values of \( M \).

It should go without saying that if I swap the places of \( D1 \) and \( D2 \), the equation must still hold in which case it becomes: $$ \mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right] \le e^\varepsilon\cdot\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right] $$

With some easy math on these two equations, here’s what we get:

$$ e^{-\varepsilon} \le \frac{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right]}{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right]} \le e^\varepsilon $$

[Please stare at this equation for a while :) It’s what the essence is and if you’re able to understand the intuitive meaning of what the equation is trying to say, my purpose of writing this blog is solved.]

Now, let’s reiterate: The mechanism \( M \) is ε-differentially private if, for all such datasets \( D1 \) and \( D2 \) that differ in only one data point, the following holds for all possible outputs O:

$$ e^{-\varepsilon} \le \frac{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right]}{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right]} \le e^\varepsilon $$

This equation is exactly what we dicussed above: If \( M \) is differentially private, then the (ratio of the) output we get out of \( M \) in case I am right handed and the output we get out of \( M \) in case I am left are “similar”, and hence we the ratio of them is bounded in the equation above. In essence, the probability of obtaining O as the output of \( M(D1) \) does not differ too much from the probability of obtaining O as the output of \( M(D2) \) (that’s what the bounds above guarantee) thus making it hard for the attacker to make deductions. Another way to write it is: For an ε-differentially private, the above holds. Hence, the two probabilities cannot differ too much from each other for the bound to hold!

[BTW, if it isn’t clear why we’re talking terms of probability here: Remember we add some random noise to \( M \) rather than returning its true output. This makes it a probabilistic mechanism rather than a deterministic one.]

And ofcourse, it follows by basic math that higher the value of \( ε \), lesser is the privacy guarantee that we get and vice versa. What’s also nice to note here is that now that we have formalized DP by means of the parameter \( ε \), we can “quantitatively” compare the privacies offered by two mechanisms \( M1 \) and \( M2 \) and say things like \( M1 \) is more private than \( M2 \) etc.

Connect everything

We have discussed the mathematical formalization and the intuitive understanding of DP but it is all still very abstract. To get a crystal clear picture, let us circle back to my handedness example.

In numbers, say,

- Total no. of individuals in the survey = 999 + 1 (I) = 1000 individuals The attacker knows the following:

- 500 are right-handed and 499 are-left handed.

- The statistic to be released is the number of left handed individuals (for simplicity and without any loss of generality, I am taking the number rather than the proportion here).

Also, let \( D1 \) = I am left handed and \( D2 \) = I am right handed and say, the ground truth is \( D1 \) which the attacker obviously does not know and which is what they intend to deduce/know by means of the survey statistic. And since, \( D1 \) is the truth, the non-differentially private output of \( M \) = 500.

DP in the picture:

Now the mechanism \( M \) here simply counts the number of left-handed and right-handed individuals with a goal to release the said statistic. And to be able to protect my privacy, we also want to make \( M \) ε-differentially private.

How do we do that?:

Ofcourse, we cannot release the true statistic and so, as part of \( M \), we need to add some noise (say \( X \)) to the counts before releasing them. The mathematical selection of this noise is the key and it should be such that \( M \) becomes ε-differentially private (which means that after adding the noise, \( M \) should satisfy the equation discussed above).

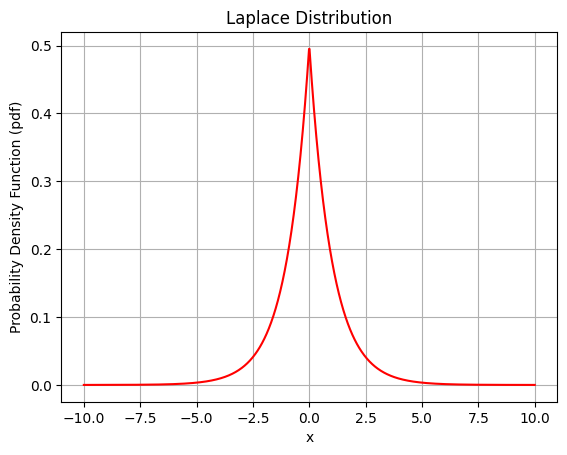

Without any long talk, I’ll tell you that we sample this noise from the Double Exponential Distribution with a scale parameter \( 1/ε \) and it does what we are looking for - this noise is capable of providing the guarantees that we promised while calling \( M \) to be ε-differentially private.

BTW, here’s how the Double Exponential Distribution looks like:

Let’s work out the Math!

Without any noise, the output \( O \) of \( M \) = 500. Let’s say we sample some noise \( X \) as told above and it comes out to be \( X = -1 \), and hence the the output \( O \) of ε-differentially private \( M \) that we publish becomes 500 - 1 = 499. Now ofcourse, using 499 as the released statistic on the number of left handed individuals, the attacker cannot conclude that I am right handed. Same goes for any value of noise \( X \). We are left to see if our privacy guarantees are satisfied with \( X = -1 \).

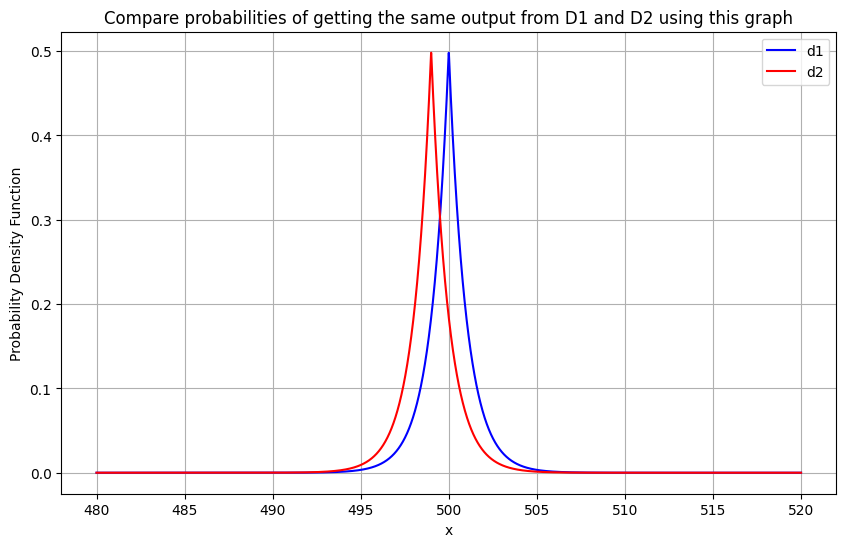

Before showing it mathematically, it might help to make sense of the graph below and realising that the X-axis shows the several values of \( O \) that can be published under DP, and that under both \( D1 \) and \( D2 \) ((shown by the blue and red graphs) the probability of each such \( O \) getting published are similar.

The Privacy Guarantees for \( X = -1 \) or \( O = 499 \):

Clearly,

$$ \mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right] = \mathbb{P}\left[X=-1\right] $$

(If I am left handed then the true \( O \) is 500 and I need to add a noise of -1 to be able to publish 499).

Similarly, $$ \mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right] = \mathbb{P}\left[X=0\right] $$

(If I am right handed then the true \( O \) is 499 and I need to add a noise of 0 to be able to publish 499).

And there we go: $$ \frac{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_1)=O\right]}{\mathbb{P}\left[M(D_2)=O\right]} = \frac{\mathbb{P}\left[X=-1\right]}{\mathbb{P}\left[X=0\right]} = e^{-\varepsilon} $$ (This simply follows from the pdf of Double Exponential Distribution with a scale parameter \( \frac{1}{ε} \) so I will not show that math here).

This clearly shows that using the noise that we used, our mechanism \( M \) is ε-differentially private. Cheers! If you were able to follow this far, you’ve already designed your first own ε-differentially private algorithm. :)